‘No man is an island - unless he is in a car’

‘When I was living in London, a Greek Cypriot friend once said to me: ‘Guernsey is a lovely place but it’s so small - when we went there my wife and I drove round it in just 20 minutes.’

I thought this was funny - I quipped back: ‘You can’t have seen all of Guernsey in 20 minutes - it takes at least 30 minutes to drive around the island.’ And so in defence of Guernsey’s compact virtues I told him: ‘The key is to get out of the car and walk - then you can see Guernsey’ - implying that on foot it would take more than a life time to discover all the islands’ nuances.’

Cars are primitive time machines. They’re quite good at transporting us relatively quickly from A to Z - (except at commuting times) - but like all time machines they cut us off from the times and places in between, giving us only superficial glimpses of what we pass by.

The more we rush the more we are subject to the omissions and constraints of time travel. In our cars we lose meaningful connection - missing out on most of the the sensory possibilities that come from exploring the places in between our departure and destination points. Life and lives pass quickly by. We miss the happenings that are possible with a slow walk. We miss engaging with nature and people. Walking is, or certainly can be, a meditation that transcends the narrow limitations of contemporary living - epitomised by our consumer lifestyles and drivers’ mindsets.

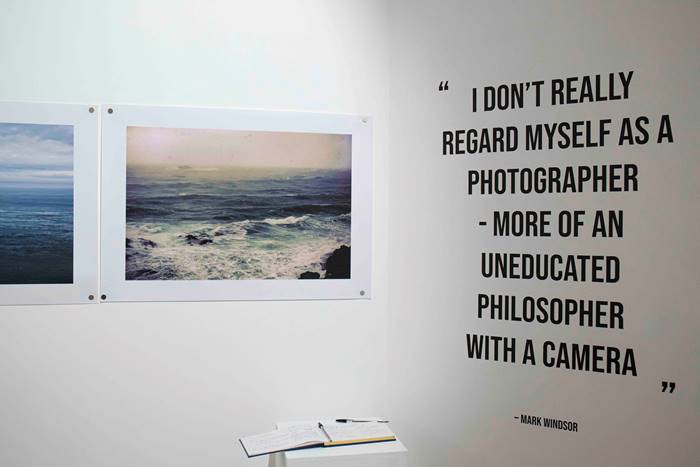

To appreciate nature and the landscape you just have to get out of the house or car and become a walker - you don’t have to be a photographer. In fact a too obsessive relationship with camera gear and obtaining the ‘right’ shot can impose its own limitations on our engagement with the environment, especially when, wittingly or not, photographers are working to visual formulae promoted by the photographic industry and media.

The real world isn’t a picture frozen in time - it’s a continually evolving process that photographs can only allude to. Photographs don’t capture sounds or smells but they can act as mnemonic devices, recalling those other sensory experiences.

The key to photography’s power is its relationship with some of the visual aspects of memory - so much of which is recalled in the mind’s eye. Photographs stimulate the visual cortex of the brain - this is why they can appeal to those who did not take them.

‘Being a photographer gives me a very good excuse to leave the car behind and to record my engagement with the Guernsey people and landscape, which in so many respects I still see in a traditional way - I guess because I am a child of the 1950s - with a visual education that took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Whether I record fragments of Guernsey’s history or figments of what I see as Guernsey’s collective imagination, photography gives gives me the opportunity to see a more nuanced Guernsey - seeing the familiar in a different light and the new or not so familiar in corners otherwise too obscure to be seen from a passing vehicle.

Guernsey born, Mark Windsor studied photography at the London College of Printing where he obtained a Foundation Diploma in Visual Communication. Mark then went on to receive a Diploma in Creative Photography, Class 2:1, 1979-82 awarded jointly by the then Trent Polytechnic and Derby Lonsdale College, studying with John Blakemore and Paul Hill. He studied for an MPhil in Documentary and Community Photography at Lancaster University 1988-90 and has practiced mostly as an amateur photographer ever since. Bar one virtual exhibition organised in Berlin he has exhibited in group and solo exhibitions only in Guernsey, and has participated in and contributed to several of the Guernsey Photography Festivals. He has also published a book of black and white photos of Guernsey: By a Different Tide.’